The Debate Over Easy vs. High-Intensity Training is a Waste of Time. Here's Why.

Zone 2, HIIT, and the Flawed Science of Endurance Training

Why do endurance athletes spend so much time going easy? Is it wrong? Should we do more intense work?

Chances are you’ve heard of the 80/20 rule of thumb from Stephen Seiler, where 80% of your training is easy. Or maybe you’ve spent time listening to health podcasters tell you that you need to do zone 2 training.

A recent review challenged this assumption, asking whether or not lots of easy is actually needed. The authors go through the underlying benefits of easy running, like mitochondrial adaptations. The lead author tweeted out a laymen summary, “Spoiler alert: I am not convinced I need to be doing Zone 2 training.” The review heavily skewed towards the benefits of high intensity training (HIT). A classification that basically means anything relatively hard.

What are we to believe? Do we need easy running, can HIT give us everything we need? Why do so many endurance athletes do enormous volumes of easy training? Let’s break it all down, from the science to the practice.

Understanding the Science

I’m a science nerd. I love it. I could geek out on physiology all day. It’s why my first book, The Science of Running, is a wonderfully messy volume full of running nerdom about training. But, as I argued over a decade ago in that book, we have to understand what research can and cannot tell us.

And that’s at the heart of this debate. The limitations of research are often to blame for skewing of training recommendations. If we were to look at the aforementioned narrative review, it falls victim to this same phenomenon.

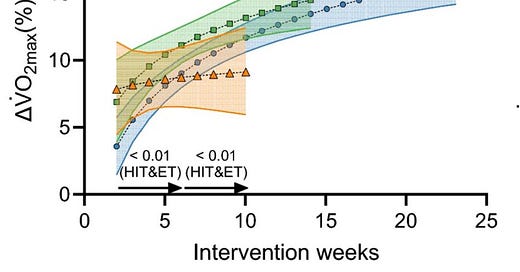

A recent analysis of the impact of easy, HIIT, and sprint interval training on performance highlights this perfectly. When we look at the impact of each training style on improvement of VO2max, HIIT usually comes out on top. You get a couple percent larger boost when compared to easy training. So we should all do HIIT, right?

Wrong. That holds over the first ~8 weeks of training. But if we look over a longer time period, the impact of HIIT plateaus, while the easy training keeps accumulating. So when we compare the two over a longer time frame, easy training catches up, and potentially surpasses the more intense work.

And this makes sense. It reflects exactly what we’ve seen in the 100 year evolution of endurance training. Easy training takes longer to work. It’s why just about every modern training paradigm starts with a longer base period of mostly easy, and more intense intervals are done in a comparatively shorter period of time to sharpen up for a big race. It’s what famed coach Arthur Lydiard noted 60 years ago. That single insight is now the de-facto barrier between old school and modern training. Before Lydiard, training reflected extremes. After Lydiard, we played with the details, but the principles are still used to this day.

This time course matters. And yet, because much of the intervention studies are done on college students in a very controlled manner, most training intervention studies are 6-8 weeks long.

Add in the fact that most studies, even those on moderately trained individuals, take people whose background is doing some jogging 3-4 days a week, and you’ve got someone coming from a background of easy running, and then giving them 6 weeks of hard intense training. What would we call that in coaching? Sharpening and peaking.

Too often in research, we neglect to understand the basic principle of training. We need a stimulus to adapt to. And if we take some people doing easy running and then continue to have them do easy running, while the other group gets a novel stimulus, of course the novel more intense stimulus will produce greater adaptations in the short term.

So much of the preference for HIIT training is an artifact of study design. This is even more evident when we look at research that is more invasive and looking at shifts in mitochondria activity. The more invasive the research, the more controlled it is. Which generally means, the more it disconnects from what is actually done in the real world. It’s why you get studies where participants repeat the same exact interval workout (or easy run) 3 days a week for 6 weeks. Something that is never done in the real world.

It’s why if we look at research that follows runners in the real world, it generally shows the opposite of the conclusion of much of the training intervention research.

In addition to the aforementioned Seiler work, Esteve-Lanao demonstrated that it was the amount of easy running that impacted running performance over a 10km race, not the amount of high intensity training. Now, you might make the claim, well that’s what elite endurance athletes do, does that apply to the masses? Thankfully, we can look at what works with college, amateur, and high school runners to see that the same principles hold.

The volumes might not be as high, but the same principles that hold at the elite level, work for the high school kid running 40 miles per week.

And finally, we often get caught in biomarker madness in research. We obsess over the mechanism, and not what actually matters: does it move the needle on fitness or performance. You can see a degree of that in this review. It goes over singalling pathways, biomarkers, and more. Which is interesting and needed…but to which we have a severe lack of understanding. As my graduate school advisor once told us, “There are many signalling pathways. And the truth is, there are dozens we haven’t found yet. So don’t obsess over the pathways. Remember the point: functional change.”

Again, that’s not to discount signalling pathways. I love them. They are fascinating and important. But they are a poor justification for understanding the impact of training. Why? Most of the studies go something like this, go run 60 minutes at X intensity, see if the pathway is activated? A single bout. Does it not make sense that a single bout of high intensity training we see lots of responses to stressors, and to an easy run, not so much? Yep. It’s the accumulation of easy volume that matters. We’ve known this in the real world for a very long time.

But more than just acknowledging the limitations of the training intervention research, the biggest caveat and problem with research reviews on training intervention is this: They ignore a century of applied science.

Understanding History

The debate over zone 2 versus HIIT is one that coaches once had. It predominated in the 1920-50s. During this era you had runners like Paavo Nurmi argue that we needed lots of long walks to build a foundation. It was only after his illustrious career that he realized he was sorely lacking on the speed side. During the same time frame, athletes who came out of the Gerschler and Reindel coaching tree thought that you needed interval training nearly every day. It was superior.

What we realized as we came into the modern training era in the 1960s is that you needed it all. And in the right sequencing. This was the major breakthrough of Arthur Lydiard. He realized that if you built a large foundation of aerobic training and then added in sharpening or interval work, you could take athletes to a higher level. And they wouldn’t get stale or “burned out” from running intervals all day, every day (which was a large fear/reality during that era.)

You can see this bounce back and forth between endurance and speed orientation throughout history. (For more, I did a YouTube video outlining this back and forth.) We essentially bounced back and forth, between emphasizing one or the other. In the early days, we argued over the extremes: long walks or 200m repeats all day. But over time, we started to argue over the mixture, working towards a happy medium in the middle.

We can see this with Lydiard’s innovation. At first, he too bounced between the extremes, a huge base, then eventually 5 days a week of intervals. Over time, Lydiard moved that down to 3 days of interval training, with more easy running, even during the sharpening phase.

Since that time frame, we’ve continued to alternate, but again we’re arguing over the minutia. We had the Peter Coe era of more intense work and lower volume in the 80s and 90s, but then a bounce back to higher volume in the 2000s. In the last decade, we had a surge of the importance of high end aerobic work (i.e., lactate threshold), while still recognizing we need lots of easy and some high intensity work to sharpen up. We’re arguing over the balance. Not whether we should do zone 2 or HIIT or anything in between. That’s accepted.

And we can see what occurs when we take a wrong turn. The 1990s were the worst decade of American running in history. We can see it at the elite level, where we often didn’t send a full team of distance runners to the Olympics because no one had the relatively modest standard. And we can see it at the high school level, where fewer kids went sub 9 in the 2-mile in the entire decade than now do in a single race…Let that sink in. What happened? We went too far in the direction of the Coe, low volume, high intensity model. It wasn’t until the rise of the internet in the early 2000s that we went back in the other direction.

Which brings me to my complaint about these arguments. They neglect this training evolution. They dismiss it. It’s not peer reviewed after all. But I’d argue that a century of coaches experimenting with an objective outcome (did my athletes run faster or not) is science. And it’s better and more robust than any short term training intervention we do.

It’s why in much of the research world, we’re having arguments over training that resemble those we had in the coaching world in the 1930s. We need to stop.

Let’s move at least to the late 21st century.

We need to follow the lead of people like Stephen Seiler or Jonathan Esteve-Lanau, who incorporate real world practice into their paradigms for studying training.

When we recognize history, we can stop arguing over whether we need zone 2 or HIIT, and instead look at refining how much and when each is needed, given the individual and their training goals.

So what?

Stop Framing it as Either/Or

Too often these debates are framed as: we need zone 2 or HIIT…when a century of training tells us: we need it all. In varying degrees. And changing it up (i.e., periodization). But we need it all.

No one in the coaching world is arguing that we don’t need easy running, or short intervals, or long intervals, or tempo work. That argument occurred in the 1930s, when we did have athletes do predominately one or the other, and often neglected the other side of the speed-endurance continuum.

Everything works to a degree

Much of the confusion comes

We had Emil Zatopek running relatively fast on dirt tracks where every single workout for weeks on end was 400m repeats. Intervals all day, every day. On the other side, we had Harold Norpoth snag an Olympic silver in the 5k in 1964 doing predominately easy running, with only a handful of one off faster efforts. Examples abound in history.

And it’s not just elites. Look at high school kids and even today, you’re going to find some who run really fast at either extreme of the speed-endurance continuum.

Some make the argument that we can’t apply research on trained athletes to novices. But I’d make the argument that you need to visit a local high school cross country coach and ask what they do with novice freshman.

Do they say? “HIIT gives us the most bang for our buck in a short time frame, so lets load them up!” No…they build a foundation with easy + strides.

The point? Anything consistently done will help people improve.

But…what we know from a century of training evolution is that a mixture of all, with mostly easy, tends to work best for the vast majority of people. It takes us to another level.

What do we need?

Lots of easy

Occasionally Hard

Vary up Hard

Repeat for months and years

That’s my simple training haiku. But if we’re concerned with training, from elite to novices. Your life and time constraints will alter your individual balance. For some, lots of easy means 30 miles per week, for others 100. Occasionally hard might mean a threshold session, long repeats, and short repeats during a week. For others, it’ll mean just one relatively intense session per week that varies.

And what does hard mean? It’s everything. From sprinting for 6 seconds to a 30 minute threshold run, and every intensity in between. Some, you’ll spend more time at, others you might visit every once in a while. It depends on your goals and training periodization. But it should all be there.

If anyone tells you that you do NOT need a specific intensity, don’t listen to them. Everything has a place.

But what we are sure of is that if you are doing 5 days a week of intense interval training, you will likely improve for a bit, but you’re training like it’s the 1930s. And if you are just going on long walks with a dash of speed, congrats you’re in the 1920s. You can do that type of training and improve. But let’s not make the argument that it’s optimal, best, or ‘evidence-based.’

This isn’t meant to target one specific review. It’s to target a much bigger problem, one that I’ve debated and written about since I was in undergrad decades ago: science can’t neglect the real world. We need to see the natural evolution of endurance training as science. It’s what Carl Sagan believed. In one of his books he made the argument that hunter gatherers were doing science when they trial and error-ed techniques to track and classify animals and plants. He wrote, “Botanists and anthropologists have repeatedly found that all over the world hunter-gatherer peoples have distinguished the various species with the precision of Western taxonomist. By this criteria hunter-gatherers ought to have science. I think they do.”

History can guide us. And as science nerd, I’d argue it guides us better than the actual science. It’s time for researchers to incorporate training history into their understanding. After all, it’s what all the pioneers in sport science like David Costill and Jack Daniels did. Follow their lead.

-Steve

I spend my days writing, reading, and reviewing scientific papers. And when I read your posts, I get the energy to get off my couch and go for a run. So good!

Great article! I have two observations and one questions.

Observation 1: It is surprising to me that scientists still try and find “the best”. It’s not that I don’t expect improvements, but it seems obvious to me that there is no one “best” but actually a lot of tools which should be adopted at various stages of training and whose effect will vary depending on the individual and their past training.

Observation 2: You hinted towards it, but time matters. A lot of these studies can do an experiment for X weeks, but it is hard to track over a longer time scale. When you do, there are so many confounding factors which you need to take into account because life is multi-variate, and it’s an output is almost never the result of one input, especially over a longer time range.

Question: Did we figure out everything with regards to training periodisation? We went from only low intensity, to only HIIT and everything in between. We did intervals as short as 6 seconds to multiple minutes. We had people running 40 miles a week and over 200 miles a week. Is there anything else we need to learn when it comes to periodisation, or are we just going to continue cycling between these two extremes forever? Personally, I think that we are better off trying to see the benefits of cross-training or other external factors rather than trying to find the “perfect” periodisation, because it is so individual there is no general “perfect”.