How do we know what works?

That’s the question that we’re after. Should we take that supplement or not? Run lots of miles or short fast intervals? And on and on.

Most of the time, that answer lies in science. We go look for a study to tell us what is better, or listen to our favorite podcaster explaining the latest research. Then, we feel good about choosing that workout routine. But as I’ve recently argued, there are some major limitations to that approach.

And if we compare what much of the scientific literature points to as important in training, it often diverges from what is done by the best athletes out in the real world. So what are we to do?

We need to see real world training as a natural science experiment. We need researchers to give credence to historical training practices to inform the research that they do. It’s not science or real world training, it’s both. And while if I pick up a book on training, like Daniel’s Running Formula, I’ll see coaches trying to link to some science. I don’t see a reference to training history in most training related research reviews or studies. Too often, it’s neglected. (This isn’t always the case, as there are some great researchers out there who try to blend in what we’ve learned in the real world).

I’ve written about this for two decades now. And instead of complaining about it…I decided to do something about it.

This is my history of training manifesto. Why? Because I think it’s the missing ingredient. The piece of the puzzle that is often overlooked, yet tells us so much in answering that crucial question: what works?

A Natural Experiment

Before we dive in, I want to outline my argument and what I hope you take away.

First, it’s that coaching runners has some unique advantages. We have an objective measure (time) that tells us if someone got faster or not. This means something on the individual level, but even more so when we look at historical trends. What works tends to stick around.

After all, if someone introduces a new training paradigm and their athletes start beating everyone doing the old way, people take notice. We can see this now with the introduction of double threshold training from Ingebrigtsen. The new way starts to spread. And if it keeps working better than whatever has been done, it sticks around.

It’s not perfect. But what we tend to see is a natural evolution of training. Over a long period of time, what works tends to stick around. And what doesn’t work quite as well tends to be de-emphasized.

Second, training emphasis tends to work as a pendulum. We tend to go in the opposite direction of what is currently done. We can see this in the battle of intensity versus endurance. We can see this throughout history. As we’ll come to learn, we go from the long walks of the early 1910-20s to the heavy interval training period of the 1940s. Then we swing back from the Zatopek intervals of the 1950s to the endurance dominated Lydiard programs of the 1960s. And on and on we go.

At first, these swings of the pendulum are large. We go from lots of long walks with a few smattering of intensity to doing interval workouts 5+ days a week. But over time, the pendulum swings are smaller. As we swung towards endurance with Lydiard, he still had a sharpening face that had between 3-5 intense workouts a week.

As we’ve moved into the modern era, we no longer argue over pure endurance or pure intensity. We are arguing over the nuance. The pendulum swinging is very small. We all agree on the same basic ingredients. Now we just debate how to optimize them.

There’s another back and forth that occurs, a battle of systematic/scientific versus artistic. Perhaps best demonstrated by the feud between Percy Cerutty and Franz Stampfl. The former was famous for training champions in naturalistic settings by feel. While Stampfl was systematic in his approach to interval training.

Additionally, we’re going to see training go from simple to complex. What I mean by this is that training had very few options (interval types) and variation (repeat similar workouts week after week), to an understanding that it wasn’t any one workout or perfect week, but how it all mixed together. As we progressed, we saw that the mixing and balancing of training over time was what really mattered, not the individual workout.

Finally, in this breakdown, I’m going to cite general trends and principles. I’ll use examples from history, and examples from a diverse array of events, mainly from 1,500m to marathon. This is not all inclusive, as it would be longer than a book.

With all that being said, let’s jump into a long history lesson. My hope is that this will serve as a helpful reference for coaches, athletes, and scientists alike.

The 19th century: The naturalistic period

In the 1860s, legendary runner Deerfoot covered 10 miles in 51:26,. When asked about his preparation he replied, “I have never trained.”

Before the Olympic era began, training was rudimentary and naturalistic. Some chose not to train, letting the difficulty of life during that time period do the work. Others reported training, but it was haphazard with little real widespread systems. The few training references we have available include longs walks, steady running, or exercise routines that we’d consider a bit bizarre now. For instance, the best miler of the 19th century, Walter George, invented the “100-up” exercise. It’s best described as repeated high knees, sometimes with a forward lean, other times leaning a bit backward. Do that until you’re tired, or about 100 times. Doesn’t sound complicated, but there was a 60 page book written by George on the exercise…

Needless to say, it wasn’t until the turn of the century that we started getting a systematic approach to training.

The Extremes: The 1900s

The turn of the 20th century represented a time of extremes. The sport was in its infancy and a battleground between amateurs and professionals was commencing.

Because of this training tended to fall in one of the two extreme camps:

Lots of long walking

Not much training with short bouts of intensity

This represents the extreme of the volume and intensity debate we still see to this day.

We can see this reflected in Len Hurst’s training advice. Hurst was one of the best long distance runners in the world in the 1890s, covering just shy of a marathon (40km) in 2:31. He said long distance runners, “will have two or three years steady work ahead of him, and must be satisfied to plod along at what, to his ambitious mind, must appear a very slow pace. I advise any amount of walking exercise…Remember, never overdo yourself or pump yourself quite out.”

Alf Shrubb (PR’s of 4:22 mile, 14:51 5k) had a similar philosophy, emphasizing lots of volume. For training for a marathon he advised 4-5 long walks a week (between 12-20 miles) and two longer runs.

On the other end of the spectrum was someone like Joe Binks, who set the mile world record at 4:16 in 1902. He barely trained. “I trained only one evening per week…spending 30 minutes...” During that one training session was short and fast sprints. A typical session included: 6x short sprints (60-110 yards), and then finishing with a 440-600 yard interval or two.”

JP Jones, who broke Binks record and ran 4:14 in 1913 trained a bit more, but had a similar low volume high intensity approach. His typical training was:

Sunday- Jog-12 miles, several sprint starts

Monday- 6-8 sprint starts, 300 full speed, jog 1 mile

Tuesday- 4-6 sprint starts, Jog 3 miles with 50 yard top speed every 800 meters

Wednesday- 4-6 sprint starts, 600 time trial

Friday- Rest

Saturday- Race

So what? This was the era of the extremes. Long and slow or low volume and fast….and not much in between. Even with the intense work, there was no interval training, as nearly everything was a one or two off fast effort.

The 1920-30s: Go Longer, plus early understanding of intervals

The next phase, during the 1910-20s, we started to see the importance of endurance training come to fruition.

First and foremost was the Finnish distance revolution. The Flying Finns was the equivalent of the wave of east Africans that dominated running in the 2000s. Led at first by Hannes Kolehmainen and then followed up with Paavo Nurmi, they took nearly all of the Gold medals in the Olympic distance events. Both Kolemainen and Nurmi had input from a coach, Lauri Pihkala.

With the Finns, you started to see two major innovations: a combining of the extremes, and the introduction of a rudimentary type of “speed work.” The Finns began their training with a period of long walks. Nurmi would walk for up to 4 hours during this phase which could be considered an early version of our modern idea of a base phase. He was building a foundation before we knew exactly what a foundation was. This was innovative at the time, as before this, athletes often only started training seriously a few months before the main competition.

Early in his career, Nurmi described his training as “one sided.” It largely consisted of walks, a few runs, and some short sprints. There were no 400s or other types of repeats.

In 1924, he adjusted his training. He kept his morning 10km walk with a handful of sprints, but added in more runs. Mid-day he’d run some short sprints (4-5 x 80-120m) with a one-off fast 400 to 1k for time. Then 3k with a fast last lap to end the workout. And then in the evening, he’d do some cross-country skiing.

As Nurmi said years later, it was a higher volume of intervals that was missing, “There were 300-600m sprints included, but there were not enough of them.” As he reported, “I had no idea of speed work.”

What we see is an extension and slight combination of the early 20th century training. The Finns and others took the long walks, but added in short sprints, and some one off steady or fast segments. But, they had a heavy endurance focus at that time. As Nurmi acknowledged himself, there wasn’t an understanding of developing endurance through “speed work.” The fitness was through accumulating training load, as we can see in his 3 times a day training. The Finns were mixing of volume and intensity, though heavily tilted towards the volume side of the equation.

The 1930s started to bring a pull back in the other direction.

Up until this point, most intense efforts were very short and often single repeats. You ran some short sprints and then maybe a 400 or 800 hard. And even when there were intervals, it was often with full recovery in between.

That started to change in the 1930s. We can see the beginning of the transition when we look at the training of American athletes Glenn Cunninghan and Gene Venzke.

Cunningham’s typical training week included short intervals of 220 yard to 660 yard in length. They were intense and low volume. Speed was the name of the game. A sample week from his coach included:

Sunday: Long Walk

Monday: Boxing and calisthenics

Tuesday: 2x660yd with 15 minutes rest (1:30, 1:23)

Wed- 4x440yd in 62 down to 58, plus some fast 220yd sprints

Thursday: Run curves, walk straights

Friday: Off

Saturday: Race

Cunningham came out of the tradition of those like JP Jones before him, with a low volume, but high intensity program. But here, you can see instead of one or the other, more of a piecing together of interval training. His contemporary Gene Venzke took a similar but slightly more modern approach. For pre-competition season, training looked like:

Monday- 10 miles easy

Tuesday 8x440yd

Wednesday- 6 mile cross country run

Thursday: 12x200 with 200 jog

Friday: 3 miles fast run

Saturday- 12 x 400

The difference between the two Americans hints at an evolution in training we were about to see. Cunningham’s high intensity, low volume training was about to be replaced by more intervals all the time. Venzke also hints at something that wouldn’t be solidified in training for a few decades, alternating long and fast, or hard and easy.

The late 1930s were the beginning of the interval revolution.

We started to see the mixing of hard and easy within the same session. In Sweden, coach Gösta Holmér developed the concept of fartlek (Swedish for “speed play”). Fartlek was an unstructured form of interval training done on natural terrain: during a continuous run, athletes would vary their speed based on feel, throwing in surges of faster pace intermixed with easier running, often using the terrain to help guide (i.e. surge up a hill, easy at the top). This free-form approach broke up the monotony of long runs and trained both endurance and speed. Under Holmér’s guidance, Swedish distance runners like Gunder Hägg and Arne Andersson used fartlek-style workouts and set multiple world records in the early 1940s.

At the same time, in Germany, Woldemar Gerschler pioneered a more scientific style of structured interval training. Gerschler – a coach and sports scientist – believed the recent Finnish and Swedish successes still lacked sufficient high-intensity work. In the mid-1930s he teamed with cardiologist Dr. Hans Reindell to create an interval regimen designed to strengthen the heart muscle. The core of Gerschler’s method was to run short bouts at a strong effort, raising the heart rate to around 180bpm, then rest long enough for the athlete’s pulse to drop to about 120–130bpm before starting the next repeat. By insisting on this precise recovery (often by light jogging or even lying down), Gerschler ensured each fast repeat placed a maximal cardiovascular stimulus without pushing to exhaustion. His intervals were usually very short – often 100m or 200m repeats run hard – because he found these distances sufficient to elevate heart rate without inducing too much local fatigue.

When asked what he thought of fartlek, Gerschler replied, “It is not exact.” Hist most famous protege was Rudolf Harbig, who set the 800m world record of 1:46.6 in 1939. The downside to this regime? It was the same, day after day, week after week. It was exact. As one of his pupils noted, “Apart from being monotonous, this training was truly tough and based, fundamentally, on a series of 100 and 200 metre sprints. Every day, more of the same.”

With Holmer and Gerschler we see that theme of calculated and scientific versus by feel and naturalistic.

For the most part, intervals won out in the 1930-50s. But it took two different paths: high volume and higher intensity. This can best be seen in contrasting two approaches: Emil Zatopek and Franz Stampfl.

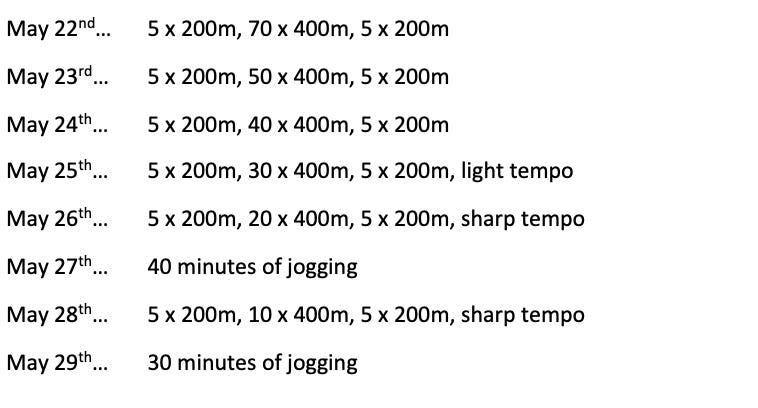

Zatopek took Gerschler’s intervals to an extreme. He stacked day after day, week after week, of high volumes of intervals. It wasn’t unusual for Zatopek to complete 60x400 every day for weeks. Or alternatively, do 400s in the morning and afternoon. In Zatopek’s own words:

“I had decided to follow this method, since it allows to train for speed and endurance simultaneously. These two are basic ingredients for runners in middle and long distances. In the first years I focused on middle distances, so speed was more important. Therefore, I used longer and slower interludes of jogging; I did short sprints (mostly 100m and 200m) with the greatest effort. In later years I prepared myself for long distances, so I trained mostly 400m and interludes of jogging were shortened by half. I also jogged a bit faster in order to gain the most endurance. Another typical aspect of my way of training is continuous increasing of the load so that my capabilities increase constantly.”

While we like to think of 200-400m repeats as intensity or “speed work,” when you are doing 30, 40, or 60 of them, they become an endurance workout. A kind of pre-cursor to today’s double threshold workouts. Zatopek didn’t record the speed of his intervals, but he did report that the tempo varied between workouts. Here’s an excerpt from his training log.

On the other side of the interval coin was someone like Stampfl, who reached prominence in the 1950s as an advisor to Roger Bannister. In fact, it was Stampfl who planted the seed that Bannister should go ahead with his record attempt when Bannister was waffling because of the weather. Bannister was famous for doing 400s. Only unlike Zatopek, he typically did 10x400 and they were fast, with the ultimate goal being to do them at mile pace or faster.

Stampfl’s training was a bit more diverse than just 400s, as a typical week for an in season miler might look like the following:

Monday- 10x400 in 60sec

Tuesday- 6x800 in 2:04

Wednesday- 10x400 in 60sec

Thursday- warm up only

Friday- 10x400 in 60sec

Saturday- 3-5 mile fartlek

As we can see, there’s 4 days of very high intensity, and one day of slightly longer aerobic work. Stampfl and similar coaches at the time brought two other key considerations. The interval speeds started slower and gradually progressed throughout the year (i.e. In the fall you’d run 400s in 68 seconds, and work them down), and there was a subtle variation in intervals. Early in the season, one of those 400m repeat sessions would have been longer repeats (i.e. ¾ mile repeats) and that fartlek would have been lengthened out to 5-8 miles.

These two different approaches get at our main theme: endurance vs. intensity. Zatopek wasn’t going on long walks, but he was accumulating a high volume of training with intervals. On the other hand, Stampfl wasn’t doing just sprints and one off distances, he was utilizing intense intervals with just a touch of endurance work to bring athletes to their peak.

Even though both sides were doing lots of intervals, what they were actually prioritizing was different. But at the same time, we can see a kind of coming together. The swinging pendulum got a touch closer.

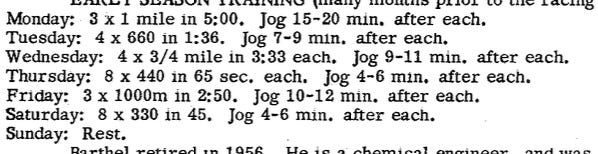

We can even see this evolution in the inventor of intervals himself. Into the 1950s, Gerschler varied his training up, including longer interval sets and more intense work. As we can see with his work with 1500m Olympic champion Jozy Barthel.

The 1960s: Innovation Time

If the 1950s were the decade of the intervals, the 1960s were a time of innovation.

Once again, this took two different paths.

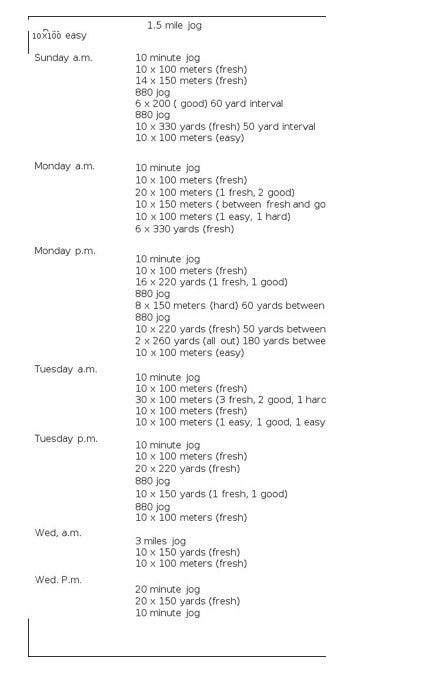

The first was by a man named Mihali Igloi, who rose to prominence in the mid 1950s coaching a trio of Hungarian runners who broke the 1,500m world record. Igloi was a strong runner himself in the 1930s when he witnessed a Polish champion running 15x200 followed by some cross-country running. He was blown away. Everyone else was doing the barely train and just run a few hard repeats and call it day. This began an experiment with intervals and training. Igloi wanted to bring it all together. As one contemporary report from the time put it, “Igloi integrated ‘interval-training’ and the Swedish ‘fartlek’ for ‘quality training’, and complemented it with a high volume of training (more than 200 Km per week sometimes).”

Igloi also brought artistry to it. Instead of Gerschler, Zatopek, or even Stampfl’s monotony, Igloi varied everything. Igloi went set by set, adjusting along the way based on what the athlete was showing them. Instead of prescribing 10x400 or 40x200, Igloi would give you a set of 6x200 at various efforts, see how you looked, and then give you the next set. Which could be a longer easy jog recovery, some 100s, a fast 800, or whatever he thought matched the training goal and what he was seeing.

Igloi took intervals to the next level by introducing greater variety and sophistication in workouts.

Although Igloi included longer intervals, most of his training was short intervals. Often broken into sets, and varying the speed, or effort within the repeats themselves.

Here’s a week from 1964 Olympic Gold medalist Bob Schul. (NOTE: Igloi didn’t prescribe times or splits. He used an effort system that was in order of increasing intensity: easy, fresh, good, hard).

During the same time period, there were a couple of other coaches who were self-experimenters who took a different approach.

Arthur Lydiard was a milkman, who decided to do crazy things with his own training. His self-experimentation led him to several ideas that would change running training forever.

While Igloi was looking at combining speed and endurance based systems, primarily through intervals, Lydiard took a different approach. He found we must develop endurance first, and through lots of easy to steady running. During the base phase, he said nearly everyone should do their own version of what was called ‘marathon training’ at the time. It’s from here that his famous 100 mile per week recommendation came from.

Now, Lydiard didn’t stop there. He brought the idea of periodization to the forefront. While, we’d seen examples of slight periodizing (longer runs and slower intervals in the fall), we hadn’t seen it put together so systematically. Following the 100mpw base phase, Lydiard prescribed a hill phase consisting of 3-5 days of hill circuits, plus longer runs on other days, and then a series of co-ordination and sharpening phases which consisted of intense interval training. In his early works, the interval period looked very similar to the training done by Stampfl, in that it had 4-5 days a week of interval training, but as Lydiard developed the idea, this slowly shifted to a more modern concept of 3 days of interval training interspersed with easy running.

And perhaps most importantly, he realized that even during this intense phase, he needed the Sunday long run to maintain the endurance he built up. Lydiard pushed our understanding of what I call the build and maintain principle. Training works like a seesaw. Do too much endurance and we lose speed, or vice versa. Lydiard’s solution was timing. He build a huge base, becoming unbalanced towards the endurance side, but he knew that if he moved to the hill and sharpening/co-ordination phase, he’d regain the athletes speed in time for their peak. He knew that if he did too much intense work, his aerobic base would erode. And if he didn’t build up speed (during the hill bounding phase) he’d never be able to be quick enough when it came to competition.

Like Igloi, Lydiard brought it together. And in all honesty, he started to bring us into modernity.

Other key figures during this training period also influenced modern training.

Percy Cerutty offered a more unconventional path to the same “endurance first” philosophy. Cerutty, an eccentric self-styled guru, preached a holistic, natural approach he called “Stotan” (combining Stoic and Spartan) training Cerutty was one of the first distance coaches to incorporate heavy weightlifting (low-rep, high-weight lifts like deadlifts and bench press) to build what he called “tensile strength.”

Cerutty was often pitted again the previously mentioned Franz Stampfl, who after his accolades with Bannister had moved to Cerutty’s neck of the woods in Australia. Cerutty and Stampfl had many spats in the media, mostly surrounding their training disagreements. Stampfl was “scientific with intervals,” while Cerutty was naturalistic. He had a disdain for regimented interval workouts and instead enjoyed having his athletes run up and down sand dunes, and circle the dirt paths of Portsea.

It was in this era that the concept of periodization truly took hold in endurance running. Instead of one monotonous training pattern year-round, coaches realized the training focus should change over the year. Lydiard formalized it, and others followed. By the late ’60s, even athletes who still did a lot of intervals (like the Igloi-trained runners) would typically have an easier/off-season period to build endurance before ramping up intensity.

Bill Bowerman, the famed University of Oregon coach (and later Nike co-founder), helped popularize and systematize these ideas. He coined the idea of hard/easy, which formalized doing a hard workout and following it up with an easier one. This alternation sometimes occurred before this era, but more common was schedules like those of Stampfl, which often had 3+ days in a row of pretty hard workouts before an easy or off day.

Bowerman and others also improved on the concept of interval training. Stampfl and others such as German coach Bertl Sumner had emphasized the importance of starting intervals slow and progressing them. Bowerman took this idea and popularized the method of date pace and goal pace, or in other words working towards your specific race pace.All of this led to what I’d say was the first “modern” training programs in the 1970’s.

By the 1970, the first truly modern training programs had emerged: high mileage endurance training year-round, interwoven with 2–3 high-intensity sessions per week, and a hard/easy cycle to manage fatigue.

The 1960-70s saw the training pendulum reach a kind of balance. The days of all long walks or 7 days a week of intense interval training were fading. We started to coalesce around how much volume and intensity we could handle.

Frank Shorter put it best:

“I’ve always had a simple view of training for distance running: two hard interval sessions a week and one long run – 20 miles or two hours, whichever comes first. Every other run is aerobic, and you do as much of that for volume as you can handle. Do this for two or three years, and you’ll get good”

1980-90s: The Intensity–Volume Pendulum Swings Back (Coe vs. Ovett and the Lure of Science)

In the 1980’s the British invasion began, no not the Beatles or any rock group, but the Steve Ovett, Steve Cram, and Sebastian Coe’s of the world took over the middle distance running scene. Just like it was a battle on the track between Ovett and Coe, it was a battle in training philosophies too.

Coe, coached by his father Peter, became the poster boy for a lower volume high intensity training approach. As Coe said, “Long, slow distance running creates long, slow runners. If speed is the name of the game, never get too far away from it.” Ovett and his coach Harry Wilson on, the other hand, took a more mixed approached that slightly favored aerobic development. Wilson was a natural evolution of Lydiard.

While Coe favored a higher intensity program, he was still running a surprisingly high volume of training. We were no longer arguing over 20mpw or 80, but instead 65 or 100 as your base phase. Similarly, we weren’t arguing over periodization. But the details of it. Lydiard had what I’d call a strict linear periodization. He went from nearly all steady running to 5 days of hills and some long runs, to 3-5 days of intensity and long runs. Sure, the long runs were there to maintain, but each phase had a heavy emphasis that was largely stuck to.

The 1980s brought more of a mixed periodization style.

We can see this in Coe’s training. Coe’s first phase of training was to establish an aerobic base, followed by an ever increasing focus on intensity. But during each phase, you had nearly everything from sprinting to 5k pace work to threshold runs and long runs. It was all there, to different degrees based on the periodization. Coe believed in making sure that each of the key intensities was covered a certain number of times every 2 weeks.

Steve Ovett, in contrast, followed a more traditional mixed program under coach Harry Wilson – one that included higher mileage (~70–80+ miles a week) and more high end aerobic work than Coe did. Ovett still did tough interval workouts, but Wilson ensured Ovett kept a strong endurance base with long runs and regular cross-country efforts. Ovett was essentially blending Lydiard-style aerobic conditioning with a healthy dose of interval training, a balance slightly tilted toward endurance compared to Coe’s more speed-centric plan. Wilson took the Lydiard strict linear periodization and made it more flexible. Instead of distinct phases, there was more of a blending of training. Not to the degree that Coe did, but you’d have hills or 200s during an aerobic phase, for example.

A typical pre-competitive week for a club level 1500m runner would be:

Monday: 5 miles in AM and PM

Tuesday: AM: 5 miles, PM 5x800 with 3min rest

Wednesday: AM- 5 miles, PM- 8 miles

Thursday: AM: 5 miles PM: 8x400 with 200m jog recovery, 15min rest, 4x150m (100m stride, 50m sprint

Friday: 5 miles easy

Saturday: 4x2k circuit

Sunday: 10 mile run

Unlike earlier cycles of training that favored an extreme of interval or endurance work, this cycle showed that we were slowly honing in on the right mix. The battle wasn’t so much if intervals should be done every day or distance running every day, but rather on how much and at what intensity. Coe favored slightly less volume and more intense workouts, while Harry Wilson and others favored slightly more volume and 2-3 intense workouts a week.

Another factor that came into play was the rise of Science. The 1980s is when we start to see training terms change and coalesce around scientific terms. Before the 80s, training was largely classified based on effort systems (think: Igloi), or by race pace. The 80s brought in science. It wasn’t 3k-5k pace work, it was VO2max training. It wasn’t tempo or steady running, it was a lactate threshold run. We start to see zones based on these concepts. The famous physiologist-coach Jack Daniels developed his VDOT system, giving coaches tables of paces for different “zones” of effort. These zones were basically based on what we could measure at the time. So, we said goodbye to simple progression of our training and instead focused on magical zones.

In the training battleground, Coe’s approach largely won out in the west. It was popularized by the easy to remember mnemonic created by Frank Horwill: The 5 pace system. Which simplified Coe’s approach to emphasizing race pace and 2 paces above and below.

Lower volume, higher intensity programs proliferated during the 1990s. And it showed.

What happened?

Well, once that crop of British runners retired, they sucked. The late 80s and 1990s were a disaster. In America, it may have been worse.Once Steve Scott who followed a more endurance based (90+mpw, 2-3 intense sessions, long steady runs) method retired, America sucked. The 1990’s with a few exceptions (mainly Bob Kennedy who trained with the Kenyans) was horrible for American pro running.

It was equally as bad for American high school running. To give you an indication of how bad it was, consider this fact:

In the entire decade of the 90s, 17 HS runners went sub 9 for a 2 mile. In the next decade, (2000s) there were over 110. Now, we have more kids go sub 9 in the 2-mile in several single races than did in the entire decade. We sucked…bad…

The 1990s marked a transitional period. On one hand, some Western programs floundered under “more interval is better” philosophies, but on the other hand, the global scene was dominated by athletes from Kenya, Ethiopia, etc., who largely adhered to high mileage and strength endurance in their training – in essence, continuing the Lydiard tradition in spirit (though with some very distinct differences and more of a fluid, mixed periodization).

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, many American coaches took note and began to return to endurance-focused training plans. Influential coaches like Joe Vigil and Bob Larsen built programs around aerobic base and threshold training. Vigil once told me that what many Americans got wrong was that we needed to push our high end aerobic development more. While the conversation was many decades ago, I remember him clearly saying, “These 4 mile threshold runs won’t do. We need to press to 8, 9, and 10 miles worth of work.” They also combined cutting edge science with historical understanding of training. For instance, Vigil prioritized aerobic development, but still took many of the sharpening workouts, strength training, and pure speed development from Peter Coe. He helped re-balance the equation.

At the high school ranks, we saw a return to an aerobic development emphasis and a more balanced approach to intensity. This was largely thanks to the proliferation of the internet. No longer did you only get your training theory from books, but you could see what everyone else was doing in training on internet message boards like Dyestat.

I experienced this first hand, starting my high school career in 1999. In fact, my high mileage came from hearing about the legendary Don Sage of York High School putting in 100 mile weeks in high school. There was a turning point that came from hearing that everyone else wasn’t putting in 30-40 miles per week and hammering out 400s and 800s. That they were prioritizing aerobic development. The resurgence in the 2000s of high school running came from the proliferation of knowledge.

Elsewhere we saw a few other influential shifts and swinging of the pendulum started to occur.

On a small message board on his personal site another former York high school phenom would spark a change that would alter training two decades later. Marius Bakken was one of the rare Europeans having some success on the professional level at the time, running 13:06 for 5k in 2004. Bakken had gone to see what the elite Africans were doing.

During the early 2000s, their training was clouded in a bit of a shroud of mystery. You’d hear bits and pieces of three runs a day, long fartleks, and progression runs, but little was concrete. Bakken traveled to Kenya and witnessed it firsthand, and took a scientific approach to his observations. What he found was that they were natural experts of aerobic development. In particular many of their fartlek, tempo, and progression runs were in the high end aerobic zone. They accumulated a comparatively large volume of training in the 2.0-4.0 lactate levels. While most europeans were doing a one off 4-6 mile Daniels style threshold run, the east Africans were doing much more. Interestingly, this was similar to Vigil’s observation.

This pushed Bakken to see how he could increase the sub-threshold work in his training. Instead of one tempo runs a week, he started to insert more sessions into his training week, aiming to get close to 30% of his weekly volume in this high end aerobic area during his base phase. And often instead of a straight tempo run (i.e. 5 miles at threshold), he’d split them up into medium length repeats with short rest (i.e. 1ks). The double threshold was born.

But Bakken didn’t just load up with threshold running. Early in his career he was coached by Peter Coe. Like Vigil, he took what worked and created a comprehensive training system. So in addition to slow recovery runs, lots of threshold, he also included 30-150m sprints to develop pure speed and speed endurance. And of course, he included more high intensity work as he got closer to racing season. Bakken also discussed balancing speed and endurance, to bring them to the right place come race day.

Bakken’s ideas didn’t reach critical mass until many years later. Why? Because it was a bunch of running nerds on his personal website, of which I was one! It was thanks to Bakken that I bought my first lactate measurement device, and experimented with increasing threshold volume. But it’s his knowledge that would set the stage for the Ingebrigtsen threshold revolution.

The other big innovation occurred when Renato Canova started sharing his training knowledge on another message board. Canova brought a nuanced, complex, and blended style of training. His focus was also on building the “aerobic house” before then creating specific endurance. Instead of a strict, linear periodization model like Lydiard, in Canova’s system everything was always there.

Canova really brought forward what I’d call the build and maintain model of training. He saw training as a balancing act, that built from general to specific, all the while never leaving anything behind. So the base training became a time for general aerobic development (i.e. lots of mileage and aerobic work) but also general speed development (pure speed, hill sprints, etc.). And then over time, we work towards specificity, while maintaining what was built.

Additionally, Canova really drove home something that was an extension of Igloi: there are no magic workouts, it’s the artistry of putting it together. Canova emphasized it’s how you manipulated the variables over time that mattered. So how are you adjusting the speed, rep distance, recovery, etc.

For instance, a progression of workouts in Canova’s style might be:

1st time: 4 sets of (5x400 with 30sec rest in 66) w/ 90sec between sets

2nd time: 3 sets of (4x600 at 66 w/ 30sec rest) w/ 90sec between sets

3rd time: 3 sets of (1k, 600, 300 at 66, 65, 63 pace w/ 50sec rest)

4th time: 4x 1mile at 65 pace w/ 90sec rest + 6x300 at 62sec pace w/ 60sec rest

We’re extending the volume of work at race specificity (66 pace) and then adding in a speed endurance component as well. It’s not just the Bowerman date pace to goal pace, but an understanding of how you are manipulating the workout constraints over time to build the specific and speed endurance to set you up to perform on race day.

Canova brought nuance and sophistication. An understanding that aerobic development is paramount, but we need to gradually connect that aerobic side to whatever race we are doing. His system is one of connection. All the puzzle pieces have to fit together.

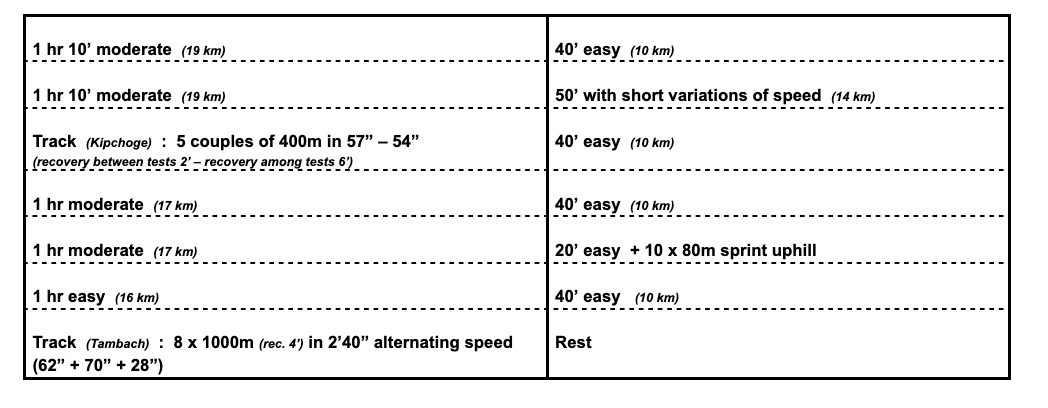

For example. Here’s a sample week for a 1,500m runner during the fundamental, or base period:

Monday: AM- 1 hr easy PM- Exercises and strength work

Tuesday: AM: 6x1k with 2min rest PM: 40min easy

Wed: AM: 1hr easy PM: 10x80m hill sprints + 3min fast continuous run

Thursday: AM: 1hr progressive PM: Gym/exercises

Friday: AM: 20min warm-up then 8km at 3:10 per km (tempo/threshold) PM: 30min easy+ mobility

Saturday: Short tests on track : 2 x [60 / 80 / 100 / 120 / 150 / 200m ] at 95% of max speed (recovery among tests 3’/4’) (recovery among sets 6’/8’)

And during the specific period, a training sample for an elite 1500m runner would be:

Canova advocated a “multi-pace” training that echoed Peter Coe’s multi-tier system, but on top of a massive aerobic foundation, and with more variation. Canova would have marathoners do 180–200 km weeks with exercises at every pace from sprint to jog in a calibrated way. This approach – essentially training all energy systems – gained traction worldwide in the 2000s.

The most recent, and arguably most discussed, evolution in endurance training is the Norwegian Method, a system that has propelled athletes like Jakob Ingebrigtsen to unprecedented levels of success. It’s a natural evolution of what Bakken was doing a few decades before. The infamous double threshold workouts often meant doing 1k or 2k repeats in the morning at just below threshold followed by shorter intervals with short rest (ie. 20x400) in the afternoon. What’s often missed is that, like Canova and Bakken before them, this model also emphasizes balancing speed and endurance. Even during the heavy threshold phase, you can see short hills, 200s, etc. included in the program. And then, just like Canova, as we move towards race preparation, we see more specific work included (i.e. 10x300 at mile race pace).

While double thresholds has been much hyped, when places in its prooper context it’s a tweaking of training ideas that had come for it. It’s now so much a revolution, but a natural iteration. The rest of the training surrounding the double threshold workouts looks like just about anyone elses from the 2000s onwards. It’s taking a traditional Daniels Threshold workout and saying, “hmm, if we split this up, and do in shorter intervals, and monitor it with precision, we’ll be able to get more of a stimulus to further adaptation.” The point isn’t to downplay it. It’s to show that early on in our training history we had big swings of training theory. As we’ve figured out what generally works, we’ve seen smaller shifts. We’re arguing over the details, not whether to do 5 days of intense intervals or lots of long walks and jogs.

So what?

As we’ve made our way through the history of training a few themes stand out:

Endurance vs. Speed (Volume vs. Intensity). This has been a debate since day one. But while we used to argue over long walks or 100m sprints, now we argue over the nuance. No one is debating that we need relatively high mileage for anything 1,500m and up anymore. We need lots of easy to moderate running. No one is arguing that we need short, medium and long intervals, or even sprints anymore. It’s all there. We need both, in the right amount. And for the most part, that balance is a bit more shifted towards aerobic development, with the other stuff seen as important but the icing on the cake.

Swinging towards a happy medium. Early in training, it wasn’t unusual to see hard intervals done 5+ days a week. That is now rare. Even during periods where intensity is emphasized, it’s rare that you see more than 3 “hard days” in a week. This has held true since Frank Shorter made his quip about training in the 1970s. What you see now, is an appreciation for more than just hard and easy. Double threshold workouts (or Canova’s special blocks) are stacking two somewhat hard workouts in the same day to get more bang for our buck. But they are done in such a way as not to be two full blown go to the well workouts. We’re learning more about the nuance of hard and easy.

Precision vs. Feel. Another common theme is this back and forth between naturalistic training and precise. It’s Gerschler’s Intervals vs. Holmer’s Fartlek, or Cerutty vs. Stampfl, or the Kenyan fartleks vs. Bakken’s precision. Both are fine. Both can work. But what you see now is an appreciation for that fact.

There are no magic workouts. It’s how you put the pieces together. Early in training, we used to focus on the best workout, or the best training week. Now, we realize that’s a fool’s errand and it’s how you put the pieces together. You can see this in our periodization models as they’ve gotten more complex and more about balancing the components at the right time. You can see this in our workout designs, as we’ve moved away from do 4x4 minutes to develop VO2max, and more towards Canova’s understanding of manipulating the variables to further adaptation.

Everything works to a degree. Look, Joe Binks ran pretty fast off one day of sprinting a week. Other runners performed well off long walks. What we often forget is that just about anything, even the craziest of workout regimes, can work! This is especially true for novices. They can do 5 days a week of intervals and get faster. Or nothing but slow jogs. But, what we know historically is that that is not best. It got left behind for a reason. So when we see a 6 week training study on 5 days a week of intervals or whatever, of course it helps them. It’s a training stimulus. But is it best? No. History shows us why.

This history lesson isn’t exhaustive. It would take a book to go through that. But what I hope you notice is that there’s a natural evolution to training. We can see how the pendulum swings, how we try new things, and even build off what’s come before. It’s not perfect. Sometimes we take some wrong turns and have to go the other way. Other times, something that worked pretty well isn’t continued exactly because it’s too hard to teach and pass along to the masses (i.e. Igloi). But what we can see are some major trends and understanding for why we do what we do.

Lastly, it allows us to put training ideas in context. And this is often missed in the health influencer and podcaster world. I’m going to use a few examples, and I don’t mean to disparage these people, they’re trying to do good work. But I want to highlight where not knowing your history gets you in a bit of a bind.

Rhonda Patrick tweeted that you could do short high intensity interval training 4-5 days a week because it was low volume. Technically, she’s correct. You can do that. But if we place it in history, what does that look like? 1930s training. We’ve moved on. It’s the same for the researchers who claim HIIT is under emphasized. If you look at their recommendations, they want to bring us back to the 1930-50s, or if I’m being more generous a version of the 1990s high school training disaster. Note: please don’t take us back there. Speaking as someone who played a small role in getting us out of that era, please don’t make that mistake.

Similarly, researchers questioned the value of “zone 2” training. While I don’t want to get into the messiness of what zone 2 is, if we look at it as easy to moderate aerobic training, we can see that we had this argument in the 1950s, where Zatopek did very little easy running. That sort of training isn’t done anymore for a reason. We haven’t debated the value of easy running since the 1960s.

On the other side of the coin are the zone 2 advocates who often frame it as the best zone ever. Well, the 1910s called with their long walks and only running and want their training theory back. Some people like Peter Attia say it’s zone 2 and zone 5. Well, we can point to a guy named Ernst Van Aaken who in the 1960s recommended essentially lots of easy and then only dabbling of faster workouts. It worked okay, but we’ve moved on. Or similarly, many in the 1960s combined aerobic training with short or medium intervals with little threshold or longer repeats, essentially going with zone 2 and 5 models. We’ve progressed since then. Ever since Peter Coe introduced multi pace theory and Canova and others extended it, we know that there are no “gray zones” in training. Everything is there. To different degrees. But if you aren’t using the full spectrum of training intensities, you are missing out.

And finally, we can place the misguided attempts at finding the perfect workout in their historical context. As many in the health influencer and scientific community have done in proclaiming things like “Norwegian” 4 x 4minutes as the ultimate workout. Again, this is middle of the 20th century thinking. Don’t fall for it. Listen to Canova and others who have put the emphasis in how we modulate the variables of the workout to get the desired stimulus and adaptation. Don’t be like health guru Bryan Johnson, who seemingly repeated this workout each week because it was scientifically “the best.” Nope, Franz Stampfl called and wants his ideas updated.

Again, I get I’m being a bit snarky. But my hope is that everyone will use this history of training to place their ideas in proper context. That scientists will utilize it to guide and inform their research, instead of ignoring a century of training experiments because they weren’t peer reviewed. And that health influencers can use this information to better inform there followers. SO that they are giving advice that reflects modern training theory, not things that were prescribed a century ago.

Thank you,

Steve Magness

P.S. This took me a LONG time to do. I had to pull out all of my old training books out of the attic and go to work. Consider sharing and subscribing for more deep dives on physical and mental performance

This is probably one of the most important pieces of running related literature that has ever come out. As a coach, this was an absolute gold mine. I could feel all the different pieces of information floating around my brain start to crystallize and organize and gain a structure and flow. I am simply a better and more informed coach after having read read this.

It was a pleasure Reading this! And, as a Norwegian; so good to read that this 4 x 4 training is old news, it is often advertised as the Norwegian method with a picture of Jakob Ingebrigtsen, who never use this method. But What I Would like to Challenge you with; I have the feeling that stress fractures have exploded in the Norwegian society after introduction of double treshfold, espesially in women. Do you know if this is the case in other running societies introducing this training?